Virtual Immigration: A Technological Alternative to Traditional Immigration in Addressing Labor Shortages

Low wage workers stay home and earn more money

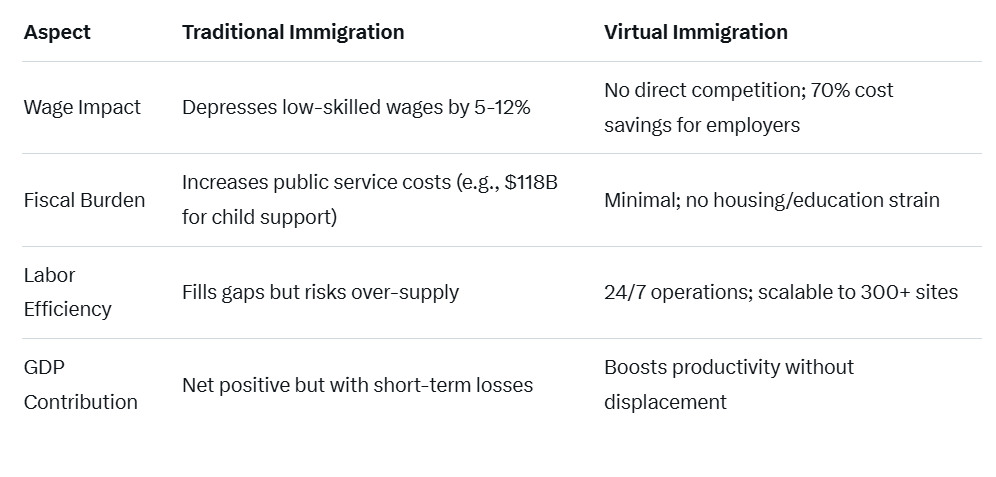

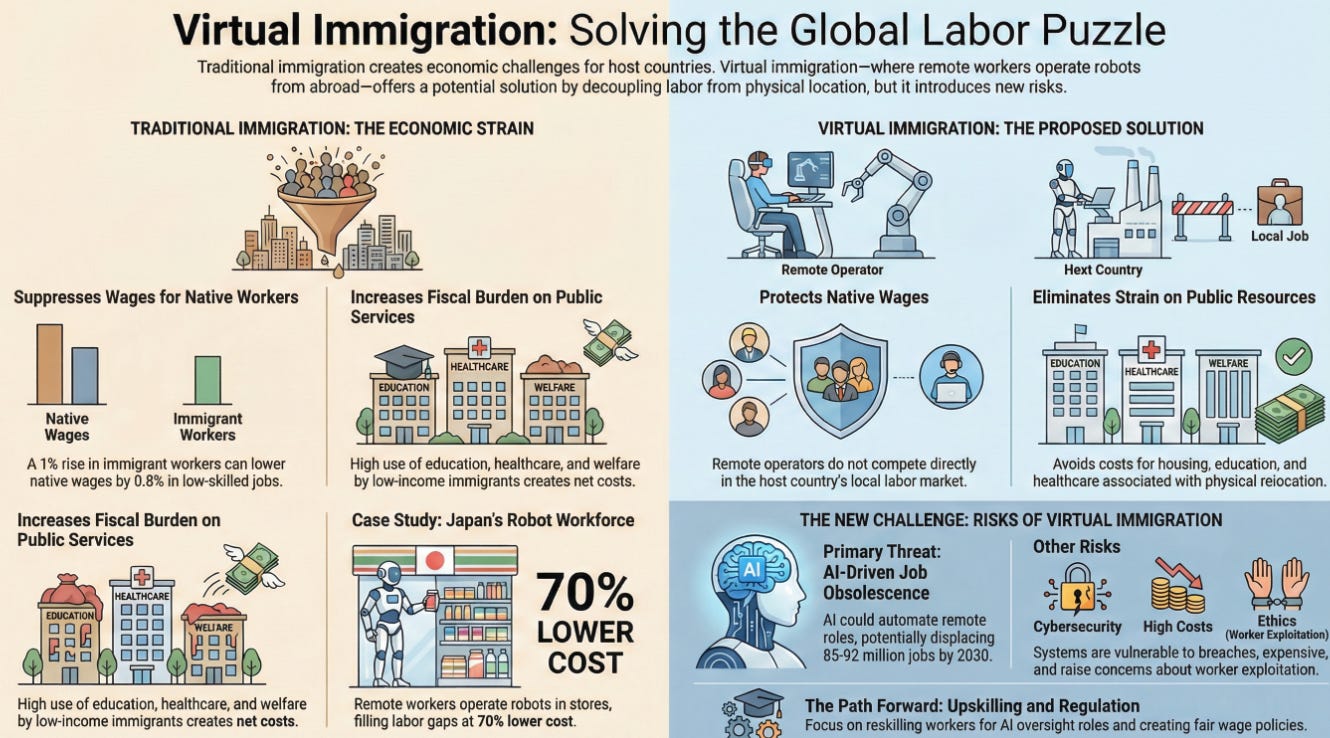

Mass immigration, while often touted for its potential to fill labor gaps and stimulate economic growth, carries significant economic disadvantages for host countries. One primary concern is wage suppression, particularly among low-skilled native workers. Empirical studies indicate that immigration can reduce wages for high school dropouts by approximately 5%, amounting to an annual loss of about $13 billion for the poorest 11% of the U.S. labor force. In low-skilled occupations, a 1% increase in the immigrant composition can lower native wages by 0.8%, potentially reducing earnings by 12% or $1,915 annually for 25 million workers. This effect stems from increased labor supply, which depresses wages in sectors like construction, agriculture, and services, distorting competition and disadvantaging native workers.

Beyond wages, immigration imposes fiscal burdens on public services. In regions with high concentrations of less-educated, low-income immigrants, native residents face net costs due to greater utilization of education, healthcare, and welfare systems. For instance, removing undocumented immigrants from mixed-status households could drop median household income from $41,300 to $22,000, a 47% decline, pushing millions into poverty and costing $118 billion to support U.S.-born children left behind. Mass deportations, conversely, could reduce U.S. GDP by up to 7.4% by 2028, shrinking the labor force in key industries like agriculture (up to 225,000 workers) and construction (1.5 million workers). These strains are exacerbated in developed countries, where immigration contributes to higher public dependency and reduced incentives for origin countries to reform, creating a cycle of economic pressure.

In Japan, these issues are particularly acute amid severe labor shortages driven by an aging population and low birth rates. The working-age population is projected to shrink by 8% by 2035 and 15% by 2045, requiring 500,000 immigrants annually to stabilize it. Yet, restrictive policies rooted in ethnic homogeneity have limited immigration, with foreign workers reaching a record 2.57 million in 2025 but still insufficient to meet demand. Programs like Specified Skilled Workers aim for 820,000 entrants by fiscal 2028, but societal resistance persists, highlighting the need for alternatives.

Enter "virtual immigration," exemplified by Telexistence's telepresence robots in Japanese convenience stores. Remote workers from low-wage countries like the Philippines control robots to perform tasks such as restocking shelves, earning $3.75 per hour—70% less than local hires—while enabling 24/7 operations without physical relocation. This model leverages global labor arbitrage, addressing shortages without the drawbacks of traditional immigration.

Virtual Immigration as a Solution to Immigration's Pitfalls

Watch the video below to see Virtual Immigration in action

Virtual immigration mitigates many economic disadvantages of physical migration by decoupling labor from location. Unlike traditional immigration, it avoids wage depression for natives since remote operators do not compete directly in the host labor market. In Japan, where labor shortages could lead to a 6.7% annual GDP drop without intervention, Telexistence's Model-T robots fill night shifts in stores like FamilyMart and Seven-Eleven, handling over 300 locations by 2025. This boosts efficiency, with robots performing repetitive tasks at costs 70% lower than domestic wages, generating surplus value without displacing local workers.

Economically, this approach reduces fiscal strains. No physical immigrants mean less pressure on housing, education, and healthcare systems—issues that cost U.S. states billions in net burdens for low-income immigrant populations. Virtual models also sidestep integration costs, such as language barriers or cultural clashes, which in Japan have fueled reluctance to expand immigration despite needing 4.19 million migrant workers by 2030. Instead, remote work via robots allows host countries to tap global talent pools, with operators in origin countries benefiting from remittances without disrupting local economies.

Data underscores the benefits: Telexistence's pilot with Astro Robotics enables scalable operations, potentially offshoring physical labor and cutting costs by allowing factories to run continuously. Broader adoption could mirror immigration's positive GDP contributions—immigrants add $2.1 trillion to U.S. output annually—but without the 1.4% GDP reduction from mass deportations or equivalent strains. In essence, virtual immigration fosters economic growth through technology, preserving native job markets and public resources.

The Disadvantages and Threats to Virtual Immigration, with Potential Solutions

Despite its promise, virtual immigration faces notable disadvantages and threats, primarily technological, economic, and ethical. One key risk is rapid AI advancement, which could render human remote operators obsolete.

Forecasts suggest AI and robotics will displace 85-92 million jobs globally by 2030, with 30% of roles automatable by the mid-2030s. In robotics, AI-powered agents could automate 57% of U.S. work hours, shifting from human-robot collaboration to full autonomy and eliminating remote jobs in sectors like retail restocking.

This threatens origin-country workers, potentially exacerbating unemployment in places like the Philippines.

Technological vulnerabilities add risks: Remote robotic systems are prone to cybersecurity breaches, technical failures, and privacy issues, as robots handle sensitive environments like stores. High initial costs—up to $300,000 for AI systems—and ongoing maintenance could limit accessibility, especially in developing economies. Ethical concerns include exploitation, with remote workers earning low wages without benefits, and reduced human connection in services, potentially alienating customers. Robots also lack improvisation, increasing workload for supervisors during malfunctions.

To counter these, solutions focus on adaptation and regulation. For AI displacement, upskilling programs could transition remote workers to AI oversight or programming roles, as AI is projected to create 170 million new jobs by 2030. Hybrid models—combining human judgment with AI—could preserve employment, with 50% of workers needing reskilling by 2025. Cybersecurity threats demand robust protocols, such as encrypted controls and international standards, while ethical guidelines could mandate fair wages (e.g., comparable to host-country minima) and benefits. Cost barriers might be addressed through subsidies or scalable cloud-based platforms, ensuring broader adoption. Ultimately, policy frameworks like Japan's evolving immigration reforms could integrate virtual models, balancing innovation with worker protections.

The Final Word On Virtual Immigration

Virtual immigration offers a compelling alternative to traditional immigration, alleviating wage suppression, fiscal strains, and cultural tensions while harnessing global labor efficiently. With economic data showing substantial cost savings and productivity gains, it addresses Japan's labor crisis without physical influxes. However, threats like AI-driven obsolescence require proactive solutions such as upskilling and regulations to sustain its viability. As AI evolves, this model could redefine work, fostering inclusive growth if managed thoughtfully.